The Skinny

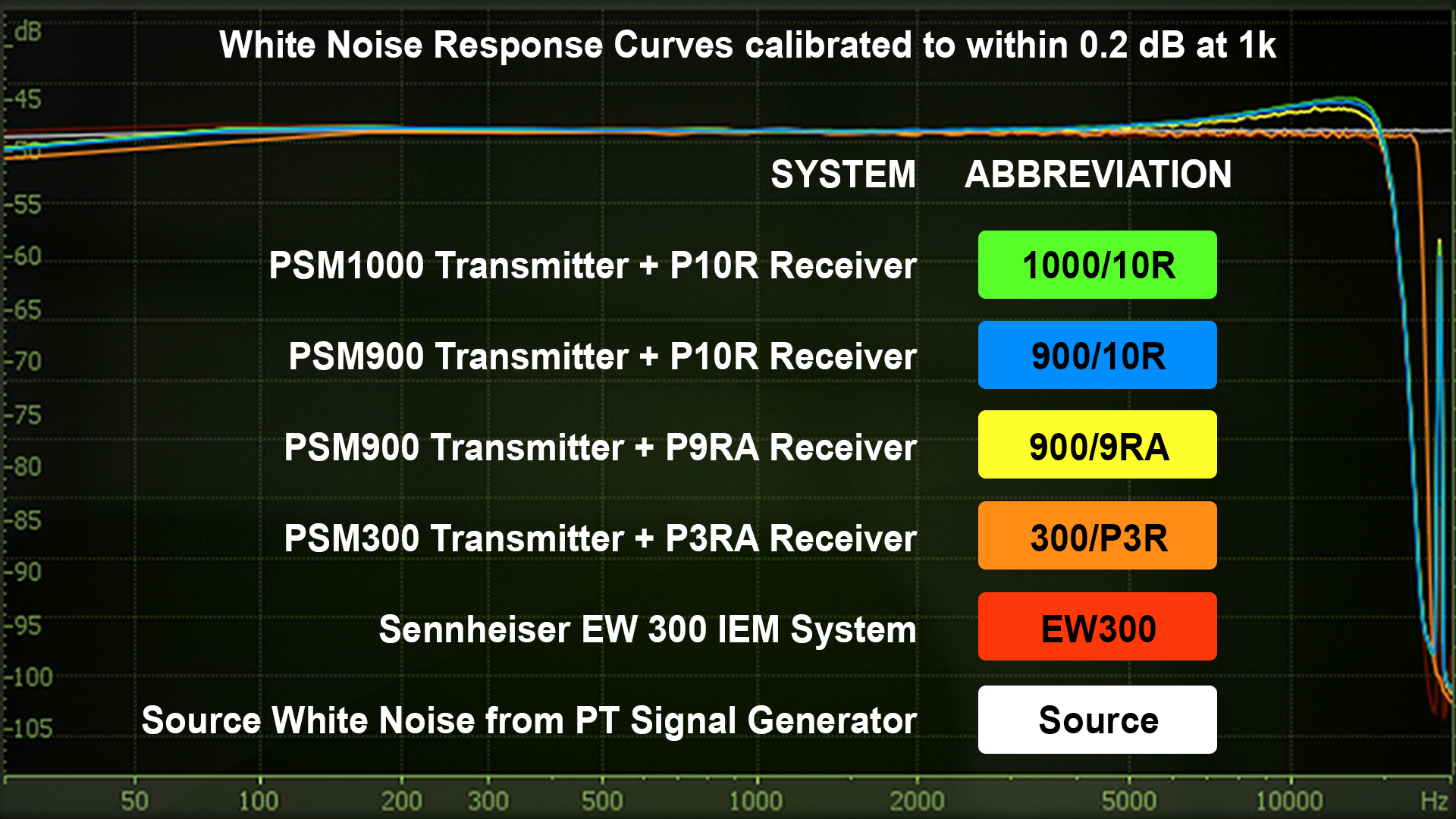

We know there are plenty more options out there when it comes to IEM systems, but the Sennheiser G3's and the Shure PSM900/1000's usually end up on most tours. Everyone talks about how low the noise floor is & how great the high end is on the Shure systems, so we wanted to finally do a side-by-side comparison (instead of tour to tour) to make it easier for anyone to truly study some of the audible differences in these systems.

Sennheiser EW300 G3 System

Price: $750 for transmitter & receiver (Purchase link: Amazon)*

I've mixed dozens of tours using these in-ear systems and they are generally sturdy, reliable, sound decent, and have held their value well since they were introduced in 2009. As you can see and hear in these tests, the top end tapers off a bit early, leaving you wanting more in terms of clarity. The low end is boosted a bit, which is nice, except it is masking the low end flutter resulting from the chip inside the receiver being unable to process the USB (upper side band) and LSB (lower side band) fast enough to distinguish left and right. The G3 packs have two antennas that it switches between - the primary is the antenna you see protruding from the bodypack. The 2nd is actually your headphone cable when it is plugged in. You will occasionally hear a "wispy" noise flick through your ears when signal drops momentarily.

Overall sound quality score: 80/100

Value score: 7/10

Shure PSM300 System

Price: $800 for transmitter & receiver (Purchase link: Amazon)*

I have not toured with this unit before, but I am very impressed with the sound quality. The only bummer is the noise floor is still significant - not quite as loud as the Sennheiser G3, but a tad brighter. The beltpack receivers (P3RA) have the same build quality of the top-end Shure systems, which makes them feel expensive despite the transmitter being much more stripped back in terms of features.

Overall sound quality score: 87/100

Value score: 7/10

Shure PSM900 System

Price: $1418 for transmitter & receiver (Purchase link: Amazon)*

This is the jump that may be hard to justify for some acts/companies. With very similar functionality to the G3 system (still no networking capabilities and similar bandwidth), the primary improvement in this system is the sound quality. The low end is tighter and the top end is considerably brighter and smoother. If G3's are the only thing an artist has heard, they won't know what they're missing. But if you've got the money, the PSM900's are much more pleasing to listen to, especially with the noise floor dropping to almost an inaudible level. It should be noted that the P9RA beltpack and the P10R beltpack both work with the PSM900 transmitter. The big difference between the two beltpacks is their A & B antennas and how the packs intelligently switch between the two. The P10R has "true diversity" meaning it has two completely separate antennas that is can choose between. The P9RA has one primary antenna and a B antenna wrapped around the first that acts as the secondary.

Overall sound quality score w/ P9RA: 92/100

Overall sound quality score w/ P10R: 93/100

Value score: 9/10

Shure PSM1000 System

Price: $5105 for a dual channel transmitter and 2 receivers (Purchase link: Amazon)*

Transmitters only come as a Dual unit, so channels are bought in pairs

With almost the same high quality audio you can expect from the PSM900, what does an extra $1000 per channel get you with the PSM1000? 1) Networkable transmitters. 2) Twice the available bandwidth. With the PSM900 hardware, you have to choose between two available bands: G6 (470-506 MHz) and G7 (506-542 MHz)... With the PSM1000, you can transmit anywhere in the G10 band (470-541 MHz). If you have a lot of wireless units, it may be necessary to utilize the full bandwidth available with the PSM1000's. Likewise, networking becomes necessary as you add more units to a system.

Overall sound quality score: 95/100

Value score: 7/10

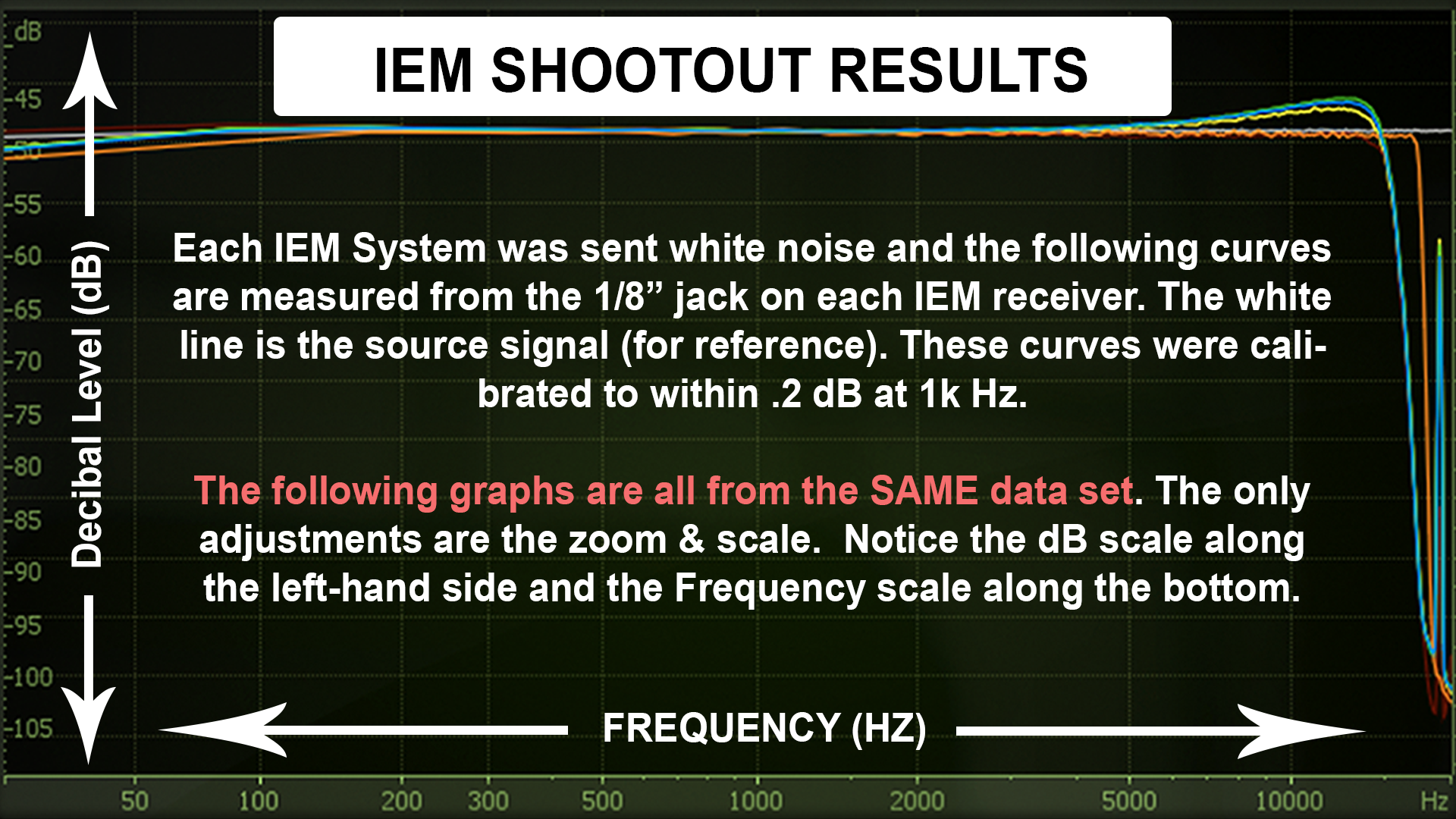

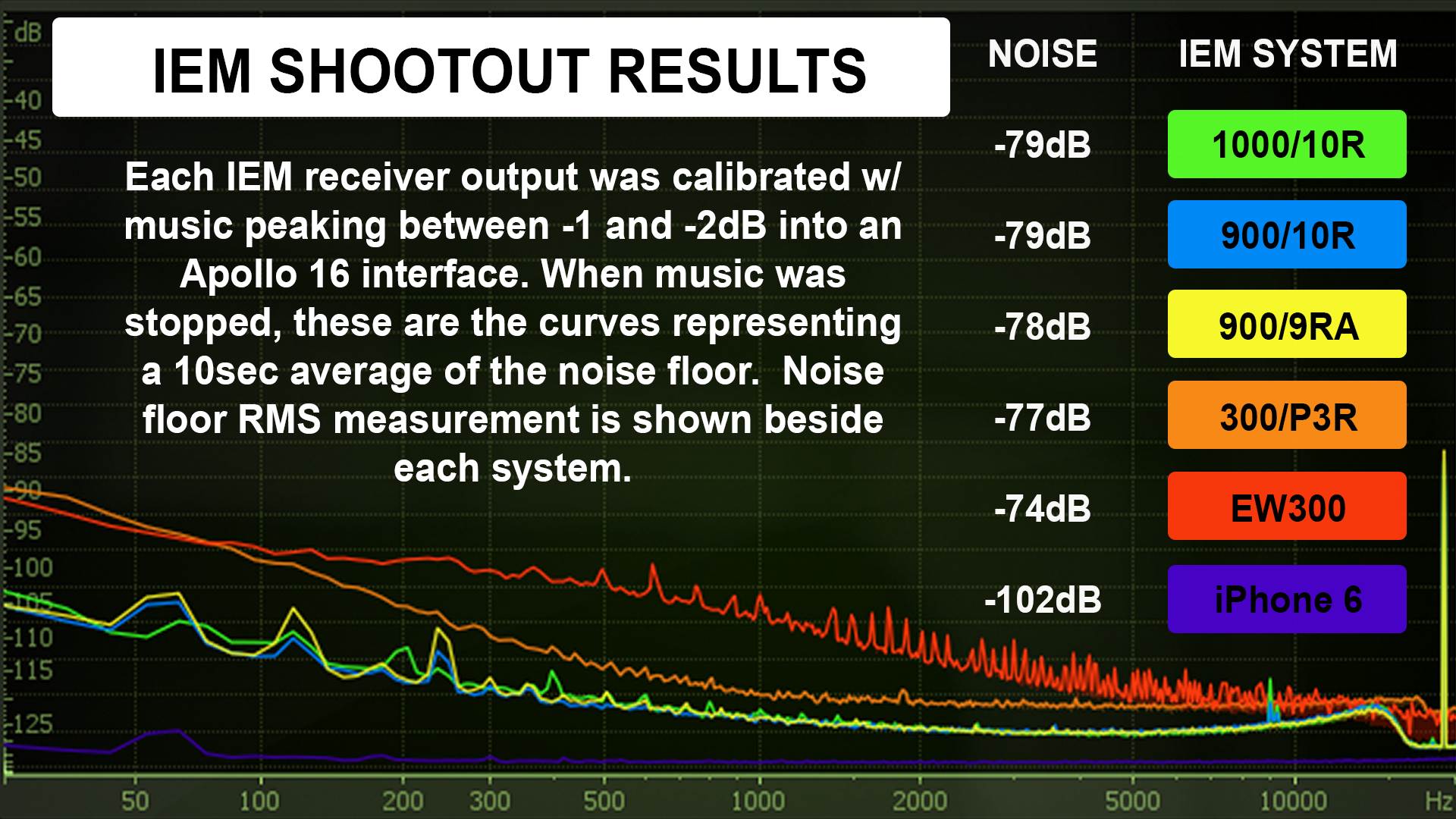

White Noise Testing Process [GEEK ALERT]

DISCLAIMER: Let me start by saying this was not a laboratory-quality testing environment. The signal chain is probably a bit long if we were being super scientific and I used a 44.1k/24bit session in Pro Tools to generate the white noise. So don't get upset that I didn't start out with a signal at 96k & 32bit...The spectrum analyzer I used only shows up to 20kHz, but you can still see and hear clear and distinct differences between the systems, most of which are happening in the audible frequency spectrum, which was the point of the test. Also factor in the video is hosted on YouTube, so the audio quality may very well have been degraded upon upload. I kept all audio recording linear (no compression) up until the upload point, so if it was not actually converted from Linear PCM during upload, you will in fact be listening to the real thing. Listening to the streamed video, I can tell you it sounds pretty darn close to the original.

SIGNAL CHAIN: White Noise was generated on an Aux channel inside a Pro Tools 44.1k/24 Bit session with Avid's Signal Generator plugin. Audio was sent out of 8 separate outputs of an Apollo 16 through Mogami cabling into an Audio Accessories DB25 patchbay, through Mogami TT patch cables back into the AA patchbay, through more custom Mogami cabling (by Redco) over to 8 panel-mounted XLR Combo jacks, out of the jacks into an 8ch TRS to XLR snake, then finally into each transmitter's balanced XLR input jacks. The PSM300 only has TRS inputs, so I used a male XLR to TRS adapter for the Left & Right into that system.

Each transmitter was set to a nominal gain setting (Unity if available) and the level of the white noise send (in Pro Tools) was adjusted to each transmitter to peak 2-3dB below the input clip signal.

To achieve readings of the receiver output, an 1/8" to stereo TRS was plugged directly into each receiver and into the patchbay, then routed into 2 available inputs on the Apollo 16. Packs were all adjusted to nominal listening volume (volume knob between 50-75%) and then 12dB of gain was added using the Trim plugin inside Pro Tools to the input signal to chart better inside Ozone's spectrum analyzer. Without the increase in gain, the noise floor fell below the viewable area inside the analyzer window. An iPhone was plugged into the same 1/8" cable and noise floor measured to ensure there was no significant noise being added by the Trim plugin that would affect the curves.

iZotope Ozone 5 was used to measure the returning white noise signal from each receiver. Levels on each pack were adjusted so that the resulting curve was matched to within .2dB at 1k. The curves shown in the images from the test represent a 10 second average.

Oh, and if you're wondering what those peaks are around 19kHz in the frequency response curves, it's not a flaw in the testing process. Those are the pilot tones sent by the transmitters that tell the receiver to split the audio into a stereo image (read more from Shure about that here).

If you have any questions that have not been answered in this rambling post, ask away in the comment section or send me an email!

*I will receive an affiliate commission if you purchase a product through the links provided. If my article helped you make a decision, I'd love it if you used my link. Thanks!

Leave a comment below - Which IEM Systems do you use or prefer?